Judaism - Sacred Stories

4.4 Sacred Stories: Revisiting Anymal Narratives

The presence, voices, and actions of anymals in sacred writings have much to teach about rightful relations with God’s creatures, and about rightful relations with the Creator. Anymals work with God in sacred narratives. They share in the unfolding of events, show initiative, intelligence, and moral fortitude, and provide guidance to humanity. A snake speaks with the first humans. A donkey admonishes a wayward gentile. Lions decline to consume Daniel.

First, this chapter explores the story of the snake in Genesis 3, then the donkey who carries Balaam in Numbers 22, and finally the story from the Talmud (Bava Metzia) about a calf, a weasel family, and the renowned Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi.

Page Outline

I. The Snake of Genesis 3

II. The Donkey and Balaam of Numbers 22

III. Calf, weasels, and Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi from Bava Metzia (Chapter 7, 85a).

Conclusion

A bright green tree python. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

The Snake of Genesis 3

(This subsection is the original work of Dr. Lisa Kemmerer.)

If snakes were in a popularity contest, among all other animals, they would surely lose. Around the world, snakes are often perceived as animals to be feared or hated . . . . [T]he reality is that most of the antipathies that surround snakes are guided by ignorance or misunderstanding. (Save the Snakes, “Why Snakes?” n.p.)

Snakes of the world suffer greatly because of human fears: Snakes that might harm are often killed, though they might just as well be left alone or relocated; harmless snakes are often killed. Because of human beings, more than half of the world’s snakes are either threatened, near threatened, or we lack data to know their survival status (“World's” n.p.). Where snakes are concerned, there is much room for improvement in our relations with God’s creatures. A closer look at the snake of Genesis 3 is a good place to start.

Despite their unwarranted reputation, snakes are critically important animals for our world. Snakes maintain balance in the food web and therefore keep ecosystems healthy. . . . Snakes are truly interesting and amazing animals, which are celebrated or worshiped in cultures around the globe. Yet, due to increased conflict with humans, many snake species are under threat of extinction. (Save the Snakes, “Mission,” n.p.)

Early Jewish (Ophite) Gnostics held snakes in high regard (Rasimus 235-36; “Ophite” n.p.) and Jewish Gnostics have an ancient and strong tradition of reading Genesis 3 without casting a shadow on the snake. Genesis 3 portrays the snake and human beings as neighbors and as neighborly. The narrative paints an image of snakes and humans pausing to chat at the garden fence. The snake is presented as intelligent. Nonetheless, the snake of Genesis 3 has someway ended up with a remarkably bad reputation.

In referring to or retelling the snake story of Genesis, the focus has long been on the snake’s presumed deliberate and successful efforts to cause Eve and Adam to disobey God, bringing the Fall of Man. This tendency has been so strong that, when Jewish scriptures were adopted into Christianity, the new religion identified the snake with Satan, or even considered the snake to be Satan (Hendeln n.p.). A fresh read of the snake narrative does not support this traditional view and instead reveals much to admire in this long and slender creature of God.

Choti Singh of Save the Snakes, with a lively wolf snake. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

Lucas Cranach the Elder, “Adam and Eve,” circa 1520-25. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

As noted, Genesis 3 portrays the snake and human beings as neighbors and as neighborly. In the conversation between Eve and the snake, the snake is described using the Hebrew word “'arum.” Forms of this word appear elsewhere in scriptures, for example, to describe the intelligence of one no less than David (1 Samuel 23:22), where the word is translated with positive connotations as “cunning.” It also appears in Job, translated as “crafty,” weighing human intelligence against the knowledge of God. Of course, humans come up short, but as with the Samuel passage, there is nothing of shame or negativity in the term—all things come up short when compared with God. The point of the Job passage is to remind humanity to be humble and focus on God, no matter how intelligent we might think we are.

'Arum also shows up in Proverbs seven times and is translated in a positive light as “prudent” and “clever”:

Proverbs 12:16:

Fools show their anger at once,

but the prudent ignore an insult.

Proverbs 12:23

One who is clever conceals knowledge

but the mind of a fool broadcasts folly.

Proverbs 13:16

The clever do all things intelligently,

but the fool displays folly.

Proverbs 14:8, 15, and 18:

It is the wisdom of the clever to understand where they go,

but the folly of fools misleads. . . .

The simple believe everything,

but the clever consider their steps. . . .

The simple are adorned with folly,

but the clever are crowned with knowledge.

Proverbs 22:3 (repeated in 27:12)

The clever see danger and hide;

but the simple go on, and suffer for it.

In each of these instances, the term “'arum” indicates intelligence with strong positive connotations. Why would the use of this term in Genesis 3 be negative while all other scriptural applications of this term are positive?

Snakes are beautiful and mysterious animals who have an unearned negative reputation. Some people have even come to fear these stunning animals, but they have more reasons to fear us than we do to fear them. (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals , “This List,” n.p.)

A closer look at scriptures affirms that there is no reason to shun the snake of Genesis 3, and that the author viewed this intelligent individual in a positive light. The dialogue centers on God’s rules regarding from which trees humans may eat, and the consequences of eating forbidden fruit. When Eve reports that God has prohibited the consumption of any fruit from a specific tree, lest they die (Genesis 3:3), the snake corrects her: “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:4–5). True to the term “'arum,” the snake clearly has more knowledge than Eve or Adam.

The Genesis snake narrative tells readers that Eve understood her neighbor to be a good source of information. She believes what the snake has said and she desires to know good and evil, so she samples the forbidden fruit, simultaneously offering the fruit to Adam:

So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. (Genesis 3:6)

Scriptures tell us that the snake knew and spoke the truth: After eating the forbidden fruit, the “eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked” (Genesis 3:7).

Hiral Naik of Save the Snakes, deftly moves a puff adder to safety. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

In knowing good and evil, Adam and Eve become aware of their nakedness, and so the Creator knows that they have eaten of the forbidden fruit. When questioned by God, Adam blames God for providing a woman, and Eve for sharing the fruit: “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit from the tree, and I ate” (Genesis 3:12). In turn, Eve blames the snake: “The serpent tricked me, and I ate” (Genesis 3:13).

But scriptures make clear that the snake did not trick Eve. Critically, the snake did not even tell Eve to eat of the forbidden fruit. The snake simply knew and spoke the truth: By eating the forbidden fruit, humanity would gain knowledge, thereby becoming a little more like the Creator (Genesis 3:5). Rather than place responsibility where it belongs, squarely on the shoulders of both Eve and of Adam (each of whom chose to taste the forbidden fruit), those interpreting scriptures have preferred to rest blame on the snake (and Eve, but not Adam—or God for bringing Eve and the snake into the picture).

Rembrandt Van Rijn, “The Fall of Man” (ca 1510). (Image courtesy of 1st Art Gallery.)

Choti Singh of Save the Snakes, gently and carefully relocates a prairie rattlesnake who is trapped in a building, protecting God’s creatures—human beings and snakes. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

Apparently, the first human beings desired greater knowledge, which scriptures tell us comes with a price, but the snake of Genesis 3 does nothing more than correct human ignorance/error with regard to the forbidden fruit. While the snake reveals information that ultimately results in Eve and Adam choosing to disobey God, it is not customary (in law or ethics) to blame those who provide information for any resultant illegal or immoral acts committed by those who receive this information. For example, if one person tells another that there is gold in a nearby home, and the informed person then breaks in and steals the gold, the informant has committed no crime.

Importantly, there is no indication in Genesis that the snake has evil intent: There is no indication that the snake intends to lead humanity astray or that the snake wants his neighbors, the humans, to choose one way or the other. The serpent simply has understanding that humanity does not have, and shares that understanding. Adults who choose to do wrong based on information acquired are singularly responsible for personal wrongdoing. In fact, any community that makes a habit of failing to hold individuals accountable for personal decisions is likely to have a problem with law and order.

In this story, God cursed all who were involved. God punishes man with thorns and prickles on the lands where he toils to produce food, and woman with both increased pains in childbirth and subordination to husbands. As for the snake, God says,

Because you have done this, cursed are you among all animals and among all wild creatures; upon your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel (Genesis 3:14-15).

Kelly Donithan, Ph.D. of Save the Snakes, holding a lovely Amazon whipsnake. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

Interestingly, punishments given by God indicate that the first human beings were akin to ignorant and gullible children in comparison with the snake, and that perhaps God intended human beings to remain in this state of ignorance and innocence. In light of who humans have proven to be—in light of what we have done with our intelligence and how this has brought about climate change, unending warfare, extinctions, and factory farming—the wisdom of the Creator is everywhere apparent. How can people best turn their faith and practice to reshape the world to bring peace (for and between all creatures), as God intended and as anticipated in scriptures?

Note that God’s curse exposes a state of enmity between snakes and humanity as a change: The snake and Eve are initially depicted as amiable, speaking together like neighbors in a community garden. Inasmuch as enmity between humans and snakes is a change, it is contrary to the Creator’s intent, and this passage certainly does not require enmity between snakes and humanity any more than it requires men to dominate women or women to suffer in childbirth. Kindness and compassion are, however, moral expectations, and in several places scriptures inform of a return to inter-species harmony:

The nursing child shall play over the hole of the asp,

and the weaned child shall put its hand on the adder's den.

They will not hurt or destroy

on all my holy mountain.

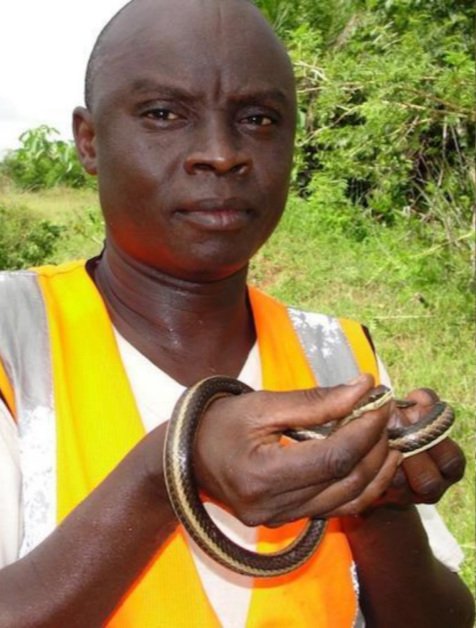

Dr. Patrick Kinyata Malonza gently holding a . (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

A careful read of Genesis 3 reveals snakes as intelligent and thinking individuals, which of course they are: Did not the Creator endow every living creature with the necessary intelligence to survive and thrive across time? The Genesis 3 narrative affirms the importance of obedience to God, and in doing so, reminds of the initial peace between human beings and snakes, which scriptures indicate will one day be restored. This seems particularly important in a world with more and more humans and fewer and fewer snakes.

Snakes, while feared around the world, are also revered and celebrated . . . . However, snakes are seriously under threat. Some snake species have become threatened due to habitat destruction, urban development, disease, persecution, unsustainable trade and through the introduction of invasive species. Many snake species are endangered and some species are on the brink of extinction. As a society, . . . we can at least respect their right to exist without harm and appreciate their vital role in maintaining Earth’s biodiversity. (Save the Snakes, “Why Snakes?” n.p.)

Faced with the obvious truth, Balaam backs down and replies, “No.” God then allows Balaam to see the angel, and the angel speaks directly to Balaam (in solidarity with God and the donkey), challenging Balaam’s cruel dominance:

The angel of the Lord said to him, “Why have you struck your donkey these three times? I have come out as an adversary, because your way is perverse before me. The donkey saw me, and turned away from me these three times. If it had not turned away from me, surely just now I would have killed you and let it live.” (Numbers 22: 32–33)

Here, while admonishing Balaam for his cruelty to the donkey, the angel informs him that, were it not for the donkey, the man would have been struck dead: The angel’s concern for the life and wellbeing of the innocent donkey ended up protecting Balaam. Hearing this, Balaam abandons his mission to curse the Israelites and, like the donkey, speaks the words that God has put in his mouth, blessing the Israelites.

In this narrative, Balaam is the “bad guy,” a human being who is abusive toward a donkey he is riding, even threatening the donkey’s life. Balaam fails to recognize the donkey as a person, as an individual with whom he has a long-term relationship. In contrast, the donkey is an agent of God and represents all that is good and wise.

Scriptures teach that God is sole proprietor of all that has been created and that God cares for every living being. Numbers 22 highlights God’s sensitivity, attentiveness, and closeness to anymals, simultaneously teaching that unkindness and violence toward anymals is unacceptable to God. In Numbers 22, God affirms that human beings are expected to be kind to other living creatures (“Beit Midrash” n.p.).

Bush Viper, one of God’s beautiful creatures. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

II. The Donkey and Balaam of Numbers 22

(This subsection is the original work of Dr. Lisa Kemmerer.)

In Numbers 22, Balak (king of Moab and enemy of the Jewish people) commissions Balaam (a non-Jewish seer or prophet) to curse the Israelites, who are camped nearby. Along the way, the donkey on which Balaam is seated sees an angel with sword drawn, which her rider cannot see. Consequently, when the donkey swerves around the angel, her irritated rider strikes her and turns her back onto the path. The angel relocates, standing between two walls, directly in the middle of the path. The donkey swerves, but in negotiating the tight space, scrapes Balaam’s foot against one of the walls. He again strikes her. Finally, the angel stands so that the donkey cannot pass, and the donkey lies down, feeling the sting of Balaam’s staff for a third time.

After Balaam’s third strike, “the Lord opened the mouth of the donkey,” and the donkey spoke to Balaam: “What have I done to you, that you have struck me these three times?” (Numbers 22:28). Balaam offers a threatening response rooted in pride: “Because you have made a fool of me! I wish I had a sword in my hand! I would kill you right now!” (Numbers 22:29). Again, speaking through the donkey, God challenges Balaam’s cruelty and his vicious threat, reminding him of the donkey’s goodness and of his long-term relationship with the donkey, which Balaam seems to have forgotten: “Am I not your donkey, which you have ridden all your life to this day? Have I been in the habit of treating you this way?” (Numbers 22:30).

Ilana and Shay, mother and son, at Freedom Farm Sanctuary in Moshav Olesh, Israel. (Image courtesy of Freedom Farm.)

Shayne was confiscated by the Israeli police after his previous “owner” was caught abusing him when he was laboring pulling a cart. Though he has terrible scars on his nose from the abuse he received as a working donkey, Shayne is a sweet and gentle soul. (Lucy’s UK Donkey Foundation, “Shayne,” n.p.)

Donkeys are still exploited for labor in many nations, including Israel. (Photo taken in Jerusalem in 2019, courtesy of Iva Rajović and Unsplash.)

Numbers 22 calls humanity to reflect on relations with anymals, especially those with whom we establish personal relations, those who fall under our power. The narrative informs that when we establish such relations we accrue responsibilities, that these responsibilities grow across time, that living creatures are God’s and not ours, that the Creator remains personally invested in each living being, and that God expects human beings to show compassion, kindness, and mercy toward anymals.

This narrative also shows that God works through anymals, and in so doing, sometimes speaks to human beings. Numbers 22 warns those who would bully or otherwise harm anymals, let alone kill them, that anymals are protected by God. And this includes domesticated, working, farmed anymals—even those whom we think must obey us, including those who appear willful and disobedient. Numbers 22 provides “a moving and eloquent plea on behalf of beasts of burden everywhere” (Regenstein, Replenish, 24). (For more on God’s ownership of creation, see 4.3.II “Creator” and for more on duties assigned to humanity by God, see 4.3.I.F “Duties Assigned by God”).

Donkeys are gregarious, inquisitive, affectionate, and very social. In their natural habitat, they travel in tight-knit herds, but around the world, they’re forced to do hard labor, exploited for entertainment, and killed for their body parts. (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, “PETA,” n.p.)

Vegan anymal activist Tal Gilboa kissing a rescued donkey with a terrible wound across their face. Gilboa helps to shape Israel's animal welfare policies as the animal rights advisor to Israel’s Prime Minister. (Image courtesy of Tal Gilboa.)

Segev, a rescued donkey at Keren Or Sanctuary in Israel. (Image courtesy of Jo-Anne McArthur, We Animals Media.)

II. Calf, weasels, and Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in the Talmud (Bava Metzia) (Chapter 7, 85a)

Talmud (literally, “study”), largely about law, is the generic term for the documents that comment and expand on the first work of rabbinic law, the Mishna (around 200 CE). The Talmud, composed of the Mishnah and the Gemara, is the source of Jewish law. The Mishnah is the original written version of the oral law and the Gemara holds rabbinic discussions on the Mishnah. There are three Talmudic tractates in the order of Nezikin (which covers law); the Bava Metzia is the second of these tractates, a book of civil law (“What is the Talmud?” n.p.).

The Bava Metzia (Chapter 7, 85a) tells of a calf, a weasel family, and a Rabbi. The rabbi is none other than Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, also called Judah the Prince, “Rebbi” (teacher par excellence), and “Rabbeinu HaKadosh” (Our Holy Rabbi). Yehuda HaNasi (135-220) was a master of Jewish oral law, portions of which he wrote down to create the earliest authoritative compilation of Jewish oral law, the Mishna (“repetition”) foundational to the Talmud (“First Complete” n.p.; “Judah” n.p.). The importance and weight of Yehuda HaNasi as a religious/moral authority in Judaism would be difficult to overstate.

Jews have frequently interpreted sufferings as brought by God because of and in response to transgressions, with the understanding that more serious transgressions bring more serious sufferings (“Bava Metzia 85a-b” n.p.). For this reason, according to Bava Metzia 85a, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi viewed afflictions as precious, even if he suffered considerably. So it was that the Rabbi “accepted thirteen years of afflictions upon himself; six years of stones in the kidneys and seven years of scurvy [bitzfarna]. And some say it was seven years of stones in the kidneys and six years of scurvy” (Bava Metzia 85a n.p.).

Why was he afflicted? What action caused this highly esteemed rabbi to suffer such misery?

Rabbi Judah HaNasi traces his personal sufferings (brought on by God) back to his own cruel, mainstream behavior. He found relief from these sufferings only through willingness to break with convention in order to express compassion for anymals: The Bava Metzia (Chapter 7, 85a) informs that, on the way to slaughter, a calf approached Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi and begged to be spared. The Rabbi responded, “Go, as you were created for this purpose” (Bava Metzia 85a n.p.).

Needless to say, the rabbi’s response was devoid of compassion. Instead of pleading on behalf of the calf and saving the calf’s life—instead of empathizing with the calf and providing aid and comfort—Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi callously sent the terrified calf along to slaughter. Rabbi Judah HaNasi accepted the fate of a calf who was being led to slaughter, though he thought the calf begged for mercy.

A wide-eyed calf suckles on an artificial teat protruding from a feeding bucket on a dairy farm in Czechia. (Image courtesy of Jo-Anne McArthur, We Animals Media.)

The Bava Metzia indicates that the Creator was displeased with this cold response, and so Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi was inflicted with painful ailments: “It was said in Heaven: Since he was not compassionate toward the calf, let afflictions come upon him” (Bava Metzia 85a n.p.). And so he suffered for thirteen years, first from kidney stones and then from scurvy.

Kidney Stones cause frequent urination; they also make urination difficult and painful, causing a burning sensation. Most of the misery of kidney stones is caused by “obstruction of urine,” which “can lead to infections—the urine becomes stagnant and static, and doesn’t drain well—and can cause the kidney to swell, which is a large component of the pain” (“Why People” n.p.). Kidney stones also move around in the kidney, between the kidney and bladder, and then out through the urethra, causing pain in the side, back, belly, groin, and testicles. Severe pain can last from 20 minutes to an hour and can sometimes cause nausea and vomiting, fever, and chills (“Kidney Stone” n.p.).

Scurvy is also painful, especially across time, and is deadly if untreated. From weakness, irritability, low grade fever, and aching legs, scurvy progresses to hemorrhaging, painful joints, tooth decay, shortness of breath, chest pain, eye irritation, headaches, and mood swings, culminating in general pain and swelling, tooth loss, internal hemorrhaging, nerve pain, convulsions, organ failure, delirium, coma, and death (“What is Scurvy?” n.p.).

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi must have suffered terribly from kidney stones and scurvy for those many years. He brought this misery on himself through indifference to a calf headed for slaughter. There would seem no stronger statement of the moral importance of kindness to anymals. And the story continues, further affirming the importance of compassion and active kindness toward anymals: According to the Bava Metzia, the rabbi suffered in these ways until he spoke up on behalf of anymals (a family of weasels).

Jimmy Stuart and family with a calf. (Image courtesy of Jo-Anne McArthur, We Animals Media.)

One day, a maidservant was sweeping out the house and came upon a family of weasels. She was sweeping the young ones out of the house when Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi noticed and said to her, “Let them be, as it is written: ‘The Lord is good to all; and His mercies are over all His works’ (Psalms 145:9).” Once again, heaven took note, but this time the rabbi had taken action to protect the vulnerable: “They said in Heaven: Since he was compassionate, we shall be compassionate on him, and he was relieved of his suffering” (Bava Metzia 85a n.p.).

Bava Metzia 85a indicates that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s afflictions “came upon him due to an incident and left him due to another incident” (Bava Metzia 85a n.p.). More specifically, God brought suffering because the rabbi failed to help a calf escape slaughter, and relieved those sufferings only after he protected a weasel family that had taken up residence in a human home.

Weasels peek out of a hole in a tree. (Image courtesy of Jan Stýblo and Unsplash.)

Bava Metzia 85a teaches that indifference to anymals and failure to act on their behalf or in ways that are sensitive to their needs is not only a punishable transgression but can bring severe consequences. Conversely, these lines of the Bava Metzia teach that those who stand against such selfish and cruel norms are to be rewarded. Importantly, in so doing, these passages indicate that acceptance of cultural norms that harm anymals, such as sending them to slaughter or eradication of “pests,” can carry serious divine retribution, while standing up against such norms brings rewards from heaven.

Apply your mind to three things and you will not come into the clutches of sin: Know what there is above you: an eye that sees, an ear that hears, and all your deeds are written in a book. (Pirkei Avot, Avot 2.1)

For more on this story, see Mindel, “Rabbi Judah the Prince.”

Many years ago, I was fishing, and as I was reeling in the poor fish, I realised, "I am killing him — all for the passing pleasure it brings me." Something inside me clicked. I realised, as I watched him fight for breath, that his life was as important to him as mine is to me. (Paul McCartney, musician, The Beatles)

Paul McCartney, proud vegan. (Image courtesy of She Magazine.)

Conclusion

In sacred writings of Judaism, the presence and voices of anymals provide moral guidance. A careful read of Genesis 3 offers much that is positive about snakes and reminds that we are to protect and tend God’s good creation—including snakes. Genesis 3 reveals snakes as intelligent and thinking individuals, which of course they are: God endowed all living creatures with the necessary intelligence not only to survive, but to thrive across centuries. This narrative affirms the importance of obedience to God. In so doing, despite traditional interpretations, Genesis 3 informs that snakes are kin, created (as was Eve) to provide Adam with companionship and to work together to serve God by tending and protecting creation. Genesis 3 recalls the initial peace between living creatures, which scriptures indicate will one day be restored. This seems particularly important in a world with more and more humans and fewer and fewer snakes.

Snakes are considered protected animals [in Israel] and serve as an important part of the ecosystem . . . harming them is against the law. (Jerusalem Post, “Israeli Health,” n.p.)

Beautiful ball python. (Image courtesy of Save the Snakes.)

In Numbers, God speaks through a donkey, reminding the faithful to serve and protect creation on behalf of the Creator, as the Creator would do, and that God has a sustained interest in the well-being of all living creatures. Bava Metzia 85a retells the experience of a highly esteemed rabbi who showed indifference to an anymal in need and who was thereby afflicted with painful ailments and found relief only after he changed his behavior so as to assist anymals threatened by humanity.

These narratives teaches humans to serve and protect what God has created, as indicated in Genesis 2:15. This narrative reveals the expectation that human beings be proactive on behalf of anymals—even against widely accepted cultural norms—and that doing so can bring rich rewards while failure to do so can carry heavy penalties.

Visitor sharing time with donkeys at Godavari Donkey Sanctuary outside of Kathmandu. (Image courtesy of Jo-Anne McArthur, We Animals Media.)

Staci with a cat at the vegan Freedom Farm Sanctuary in Moshav Olesh, Israel. (Image courtesy of Freedom Farm.)

Recommended Sources

Kemmerer, Lisa. Animals and Judaism. (Amazon, 2022, http://lisakemmerer.com/publications.html.)

“As Summer Begins, Ministry and INPA Remind Public that Snakes are Protected.” Gov.il: Departments: News: Ministry of Environmental Protection. Oct. 6, 2020. https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/snake_capture.

Morgan, Diane. Snakes in Myth, Magic, and History: The Story of a Human Obsession. Praeger, 2008.

For more books on snakes, see suggestions at Save the Snakes: https://savethesnakes.org/store/Books-&-Postcards-c33011307